Okay, so we all know that Solidity DeFi projects don’t do arithmetic on real numbers. But 18 decimals fixed point arithmetic is a pretty good approximation, right? It’s close enough that we don’t need to worry, at least most of the time. Right?

No.

And I always have difficulty explaining this to people. Real, continuous mathematics is in a class of its own. There may come a day when I explain this in great detail, but it is not this day!

Instead, I’m going to look at a really simple example that shows the chasm between real arithmetic and fixed point arithmetic with 18 decimals.

If you’ve ever read a DeFi whitepaper I bet you’ve noticed that the mathematics implicitly assumes that we’re dealing with real numbers. For instance in the original Uniswap V3 whitepaper you see these equations:

And then they’ll use these equations to derive

(See the Appendix below for the derivation)

All this assumes real arithmetic because the algebraic manipulations required do not hold for integer arithmetic. It is simply not the case that even

This is super obvious for and , but even with 2 decimals we find that:

15e2 * 1e2 / 7e2 == 2.14e2

i.e.

but

1e2 * 1e2 / (7e2 * 1e2 / 15e2) == 2.17e2

i.e.

We are lulled into thinking that the Solidity implementation, which has to use fixed point arithmetic, will be close enough. We think “perhaps it will have the odd rounding issue, but it will be close enough”.

Wrong

Here’s a simple example that shows this just isn’t true. You have to treat fixed point arithmetic very carefully. Let’s start.

In real arithmetic the following is always true.

Nothing to argue with here.

So you might think that we would get results very close to

1e18 in Solidity most of the time.

Let’s assume the following code.

function mul(uint256 a, uint256 b) external returns (uint256) {

return a * b / 1e18;

}

function div(uint256 a, uint256 b) external returns (uint256) {

return a * 1e18 / b;

}

function recipMul(uint256 x) external returns (uint256) {

return mul(x, div(1e18, x));

}If you want to try this in Chisel it just simplifies down to:

➜ uint256 x = <number>;

➜ x * (1e36 / x) / 1e18;Now let’s put it in a table.

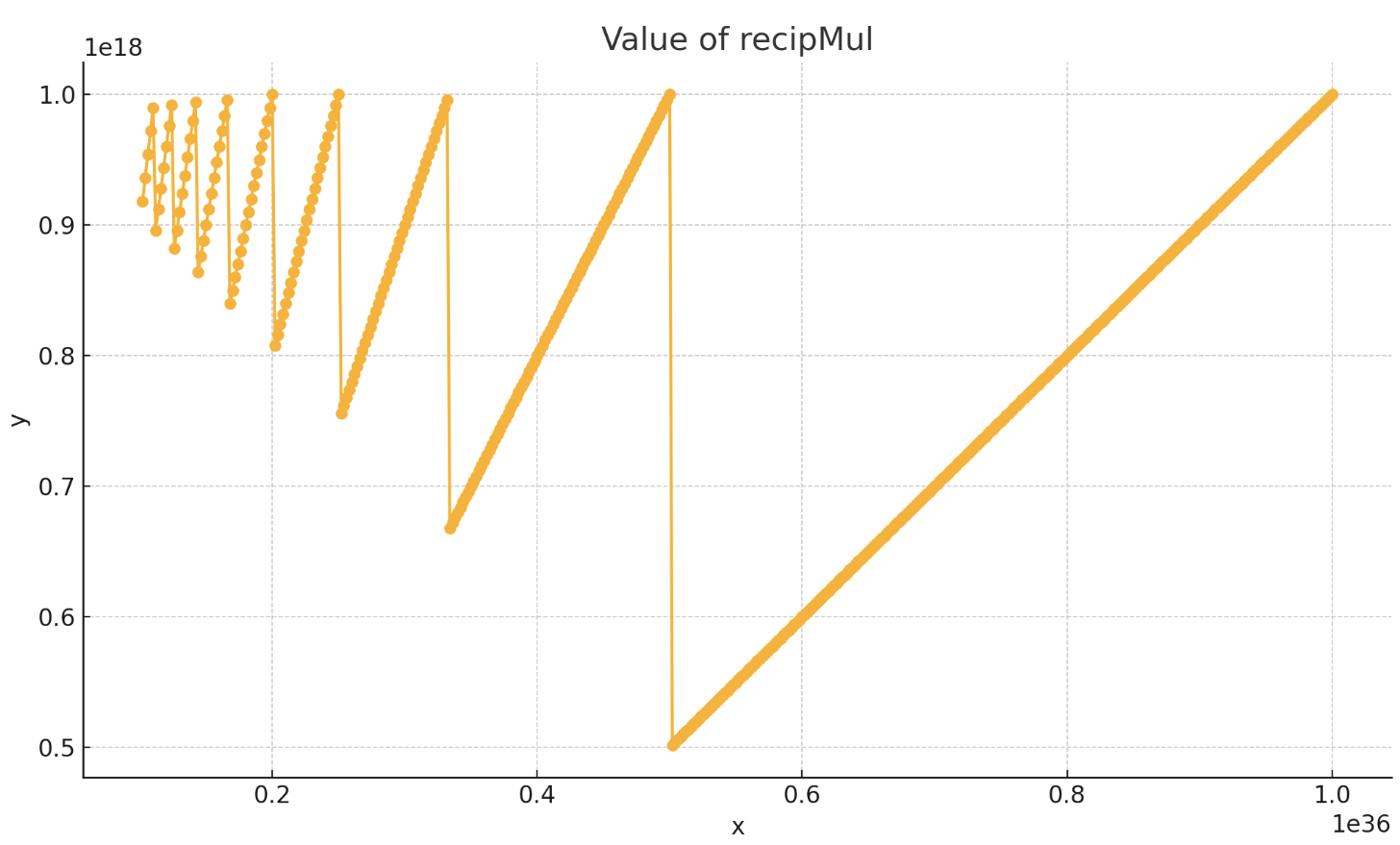

| x | recipMul x |

|---|---|

1e18 |

1e18 |

| … | … |

100_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

1.000e18 |

120_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

140_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.980e18 |

160_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

180_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.900e18 |

200_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

1.000e18 |

220_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.880e18 |

240_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

260_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.780e18 |

280_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.840e18 |

300_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.900e18 |

320_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

340_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.680e18 |

360_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.720e18 |

380_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.760e18 |

400_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.800e18 |

420_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.840e18 |

440_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.880e18 |

460_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.920e18 |

480_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

500_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

1.000e18 |

520_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.520e18 |

540_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.540e18 |

560_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.560e18 |

580_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.580e18 |

600_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.600e18 |

620_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.620e18 |

640_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.640e18 |

660_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.660e18 |

680_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.680e18 |

700_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.700e18 |

720_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.720e18 |

740_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.740e18 |

760_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.760e18 |

780_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.780e18 |

800_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.800e18 |

820_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.820e18 |

840_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.840e18 |

860_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.860e18 |

880_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.880e18 |

900_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.900e18 |

920_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.920e18 |

940_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.940e18 |

960_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.960e18 |

980_000_000_000_000_000e18 |

0.980e18 |

Everything gets a bit screwy when you get to numbers like 120,000,000,000,000,000. Yeah, this is a big number, but it’s not that big. It’s “only” 120 quadrillion and it fits in 117 bits.

mul and div (as defined above)1e36 (120 bits) in the

expression 1e36 / x above.Notice that the result we get is 0.96e18? That’s pretty

inaccurate already. And as we go down the list of values, in 10

quadrillion increments, we see that we get a “sawtooth” pattern. The

value gets more and more inaccurate and then suddenly “jumps back” to

being 1e18 again.

I used ChatGPT to plot these numbers (this time using a smaller increment) and got this

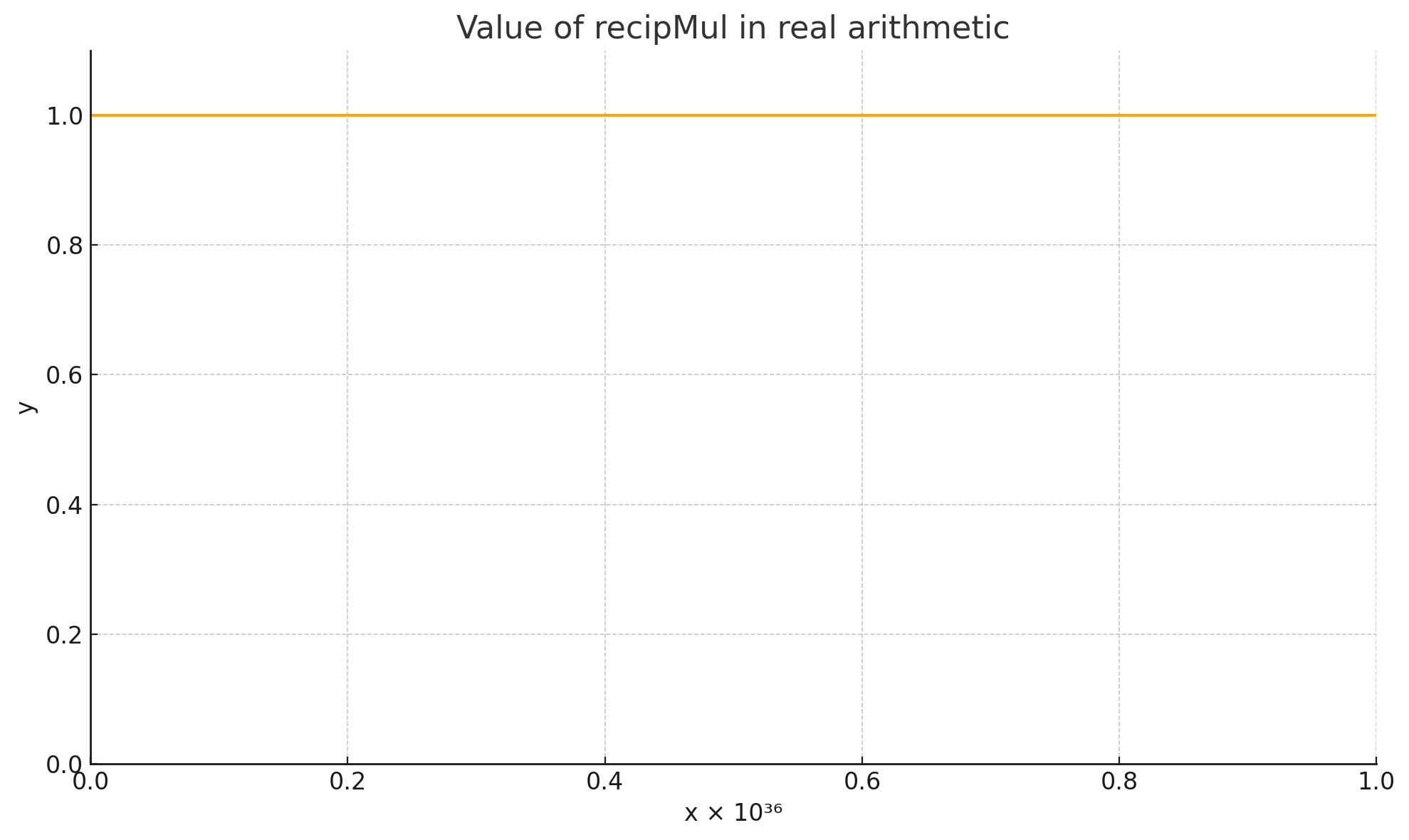

And what would this look like in real arithmetic?

Pretty different, huh?

How many bugs are lurking out there on the margins of fixed point arithmetic?

The derivation of is as follows. For clarity I’ve showed way more steps than you’d normally see in a paper.

The point is, none of this algebra actually holds for integer arithmetic. It assumes real numbers.